Let’s face it. In the context of the vastness of the universe, we, the whole human population, are about as insignificant as a colony of amoeba in a puddle of water at somebody’s backyard after a rainy day. The significance of our existence would then seem like a thin invisible thread in an unimaginably infinite fabric of space. Should we then give in to the futility of our role in the world we live in? Does our life as individuals have any meaning? Or, are we destined for something far greater than the mere biological evolution of our species?

Let’s look at that amoeba. Imagine one in a patch at the water’s edge of Lake Michigan. With it were countless others that are each an exact copy of itself after countless cell divisions in a blink of an eye - by human chronological reference, that is. But the amoeba was proud of what it had achieved. So one moonless night it looked at a faint glimmer of light that was on the other side of the lake. It knew it was far away but it was curious. It decided that it must go to where that light is. It is a challenge it couldn’t resist.

We scale that story up many, many millions of times to our level and within the context of just the last few hundred years of human history. Have we not contemplated reaching for a similar distant glimmer of light? Our ancestors would look up at the glowing moon each nightfall, and with their naked eyes pondered even more at the thousands of faint lights farther out. Just like the amoeba we had let our unfettered leap of imagination soar to the high heavens – reaching for the stars. Our evolutionary path has taken us not only to great physical wonders of anatomy but to levels of intelligence that gave us calculus, the languages, powdered milk, powered flight and a few other things. That is the good news. However, the amoeba has a better than fair chance of reaching the other side of the lake than our reaching the nearest star. It is a practical impossibility for any human to reach Proxima Centauri, least of all in one’s lifetime. A journey undertaken by multiple successive generations of space travelers is a fantasy. Let’s put this one to rest. It takes four years for light from that star to reach us (at a staggering speed of 186,000 miles per second). The laws of physics will not allow any object to attain that speed. Let’s assume we can multiply our current launch capability for spaceships from earth at hundreds of times, it will still be a fraction of the speed of light, so it will still take future astronauts hundreds and hundreds to thousands of years to get to the nearest star. Then there is the issue of cost. There is not enough wealth and resources, let alone the international will, to finance such a voyage. As population grows the future world economy will be no better and people will not pay for something they will not see completed in their lifetime. No one plants a tree that will bear fruit beyond the grower’s lifetime. We cannot also ignore the possibility that before such an adventure we will have destroyed our world through war, natural depletion of resources (food in particular), various geological catastrophes and diseases, etc. And let us not forget the inevitable asteroid strike – an event that has occurred with recurring regularity in earth’s history. One strike actually changed the entire makeup of how life evolved on this planet over sixty millions years ago.

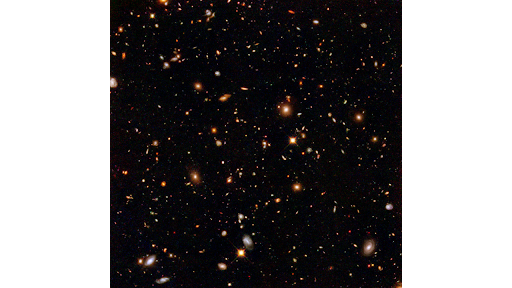

So what is the meaning of our existence? Here we are in a middle orbit of a solar system lorded over by a small star that is one of billions of others that make up a pinwheel-shaped averaged size galaxy. From the perspective of our own Milky Way galaxy alone, planet earth is a grain of sand on a beach along an infinite shore line. Then we find out our galaxy is an average size island of stars scattered around with billions of other galaxies that we perceive as the known universe. We are therefore as significant as a billionth of a grain of sand trying to determine the shape of a sand dune. True. So, should we then lead our individual life with purposeless futility?

Let me bring in the amoeba again. As organisms go, the amoeba is about as simple as it gets. It feeds on other simple organisms that could be harmful to us. In turn the amoeba is also food for other slightly larger organisms and the process cascades upwards to more complex life forms. The bad news is that this type of protozoa also causes amoebic dysentery that kills thousands of people and sickens millions more, particularly in under developed nations, around the world every year. It is not as insignificant as we might think. Meanwhile, at our level, the pages of history are filled with individuals who have left indelible marks, good and bad. Pages of our history have been soiled with the likes of Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, Pol Pot and many more. On the brighter side of history we were given Aristotle, Abraham Lincoln, Albert Einstein and Mother Theresa. And let’s not forget ordinary folks around us - everyday people - who volunteer at the hospices, do rescue work, serve at churches, etc.

Significant or not there is quite a lot to think about as to our place in the universe. We may not reach the stars but we now know so much about them. All the heavy elements we have here on earth were made from exploding stars. That led one cosmologist to declare that we are literally made of stardust.

Iron, potassium and sodium, etc. that are in our blood could ONLY have come from a supernova explosion billions of years ago. Our sun, in fact, could be one of the third generations of stars created by such an explosion. Are we then a product of chance, a random roll of a cosmic dice?

It would take a series of lucky rolls of the dice to make a habitable planet.

It is therefore not a difficult thing to say that, indeed, we - all of us - are here for a reason because to think otherwise would mean we relegate ourselves to the seemingly insignificant existence of an amoeba. But as you read above, that amoeba is not so insignificant after all, is it? For that reason we therefore ought not believe in our insignificance. Instead, we must marvel that we have a mind, or rather that we were endowed with a mind that is more powerful than the most massive computer system ever built. Just the last few seconds that you pondered that, no computing power can match the breadth and scope of what you just thought about. Everything else would then seem insignificant. Once we set our mind to think that, we are significant.

No comments:

Post a Comment